Comets are small, irregularly shaped objects whose orbital semi-major axis (average distance to the Sun) takes them beyond the orbit of Pluto. They are made of ice and rock ("dirty snowballs"), and they change brightness dramatically as they approach the Sun.

Comets are of tremendous interest to astronomers because they hold the clues to the conditions in the very early solar system. They represent the unaltered material out of which the [outer] solar system formed, and therefore can tell us about star and planet formation and evolution.

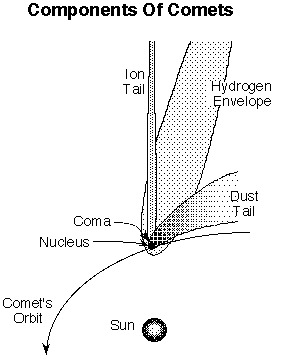

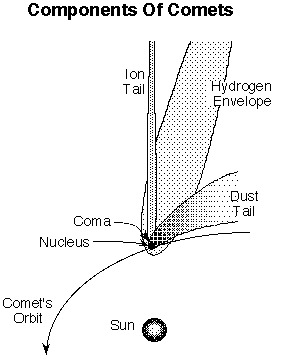

There are several parts of a comet, shown in the figure below:

Comet West (1975). Image copyright by John Laborde.

Comet Hale-Bopp (1997). Image by Malcolm Ellis.

The two tails of a comet (and the reason they go in slightly different directions) are described here.

The different parts of the comet vary tremendously in size:

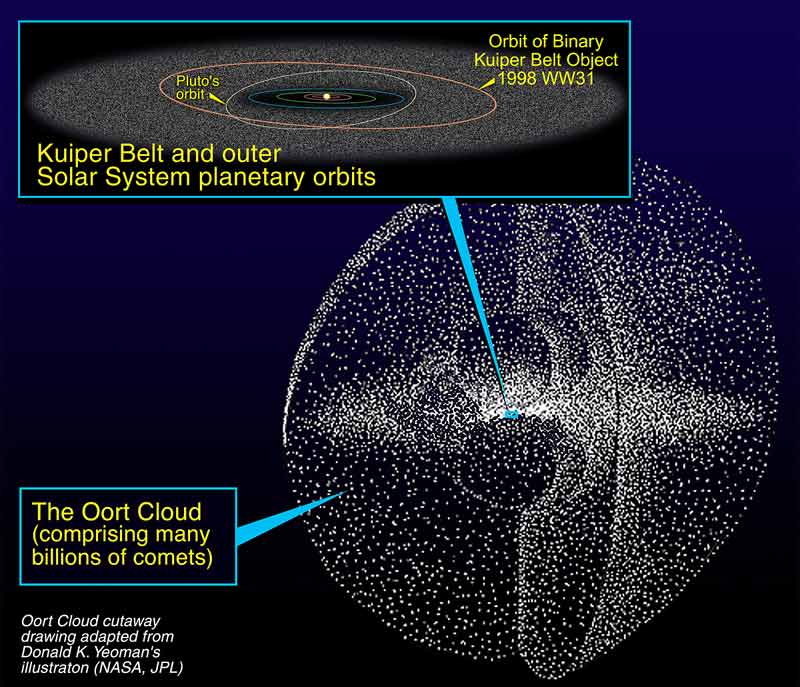

Comets come from two different reservoirs:

The Kuiper Belt is located beyond the orbit of Neptune (~ 30-100 AU), and the objects there orbit the Sun in the plane of the planets. The short period comets (orbital period ~ 100 yrs or less) are thought to originate in the Kuiper Belt.

The first Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) was discovered in 1992. As of yesterday (4/13/04), there were 775 known KBO's, and it is estimated that there are tens or hundreds of thousands out there. The study of KBO's is in its infancy, but these objects are extremely important for telling us about the conditions in the early solar system.

Image of 1992 QB1, the first Kuiper Belt Object ever discovered, from http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/faculty/jewitt/kb.html.

Blink sequence of 1995 WY2, showing how these objects are discovered, from http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/faculty/jewitt/kb.html.

The Oort Cloud is a spherical cloud of comets located much farther away: few hundred to thousands of AU's away. These comets orbit the Sun from any direction, and are the long-period comets.

What about Sedna, the new Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) that was discovered last month? It is currently roughly 90 AU from the Sun (near perihelion), but its orbit is highly elliptical. Thus it will eventually get about 1000 AU from the Sun! It may be an object that is representative of a whole population of objects that is trapped between the Kuiper Belt and the Oort cloud. No one knows for sure (yet!).

A comet is not "active" throughout its entire orbit around the Sun. Only when a comet passes relatively close to the Sun - within roughly 3-4 AU - does the comet "turn on" and emit gas and dust. During the rest of its orbit, the nucleus is inactive and consequently difficult to detect. It would resemble the comet nucleus that you made in lab last week.

Illustration by Mary Urquhart, http://lyra.colorado.edu/sbo/mary/comet/general.html.

Over time, particularly for a short-period comet that would come near the Sun fairly often, the nucleus becomes more and more like a rubble pile. Here is a clear explanation of how that happens.

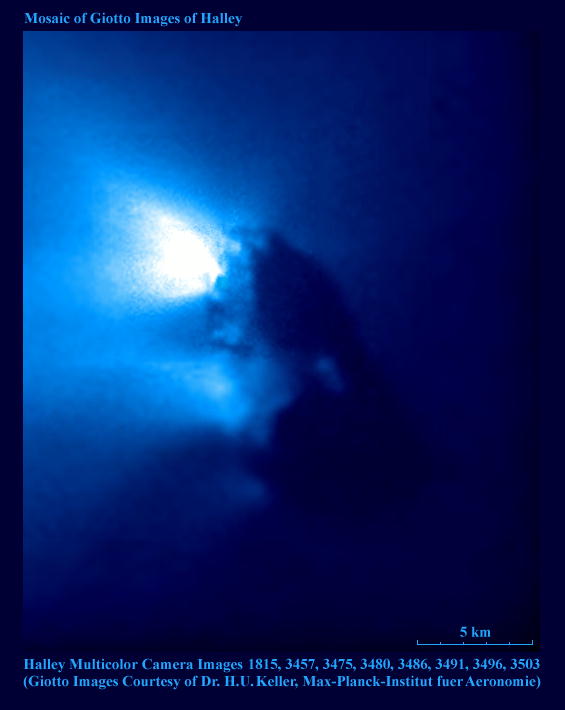

The black, inactive part of the nucleus of comet Halley is probably a rubble mantle.

Image taken with Giotto, a European spacecraft, in 1986. The nucleus measures roughly 16 x 8 x 8 km, and only about 10% of its surface is active.

Comets DO impact other objects in the solar system!! We saw evidence of this first-hand in July 1994, when Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 crashed into Jupiter. This comet was discovered in 1993, and it appeared rather odd-looking in the discovery image.

Image taken from the Kitt Peak National Observatory on March 30, 1993, shortly after it was discovered.

After calculating the orbit of SL9 (and running it backwards), it was realized that the comet passed very close to Jupiter in 1992. The strong gravitational influence of Jupiter caused the comet to break up into 22 fragments, each of which behaved as "mini-comets" on a crash course for Jupiter.

Image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope in January 1994.

Here is a web site that contains numerous images of Jupiter after the impacts, which took place in July 1994.

Numerous comets have also been discovered crashing into the Sun using the European-American spacecraft SOHO, which is designed to study the Sun. One of the instruments uses a coronagraph, which blocks out the central part of the Sun so that the tenuous, outer region called the corona can be studied. Many comets are seen plunging into the Sun, such as the one shown in the below image.

SOHO image (taken in December 1996) courtesy of NASA.

On the SOHO web page there are links to movies (see "Gallery" and then "LASCO") of comets crashing into the Sun.

Why do you think comet impacts anywhere in the solar system would be important?