Jupiter has four large moons that are known as the Galilean satellites, named after their discoverer (Galileo). Here is a description along with the original drawings done by Galileo.

Jupiter's 4 large moons are, in order of increasing distance from Jupiter:

We have tides on Earth, and these tides are caused by the gravitational interaction between the Earth and the Moon (and to a lesser degree, the Sun). The Moon pulls on the Earth. The side of the Earth closest to the Moon will feel a greater gravtitational force than the side farthest from the Moon, since gravity is a function of distance. This difference in gravitational force felt between the two opposite ends of the Earth cause the Earth to bulge out along the equator. The water in Earth's oceans tends to flow towards the two regions below and opposite the Moon, resulting in more water at those locations. Here is an animation to show you how it works.

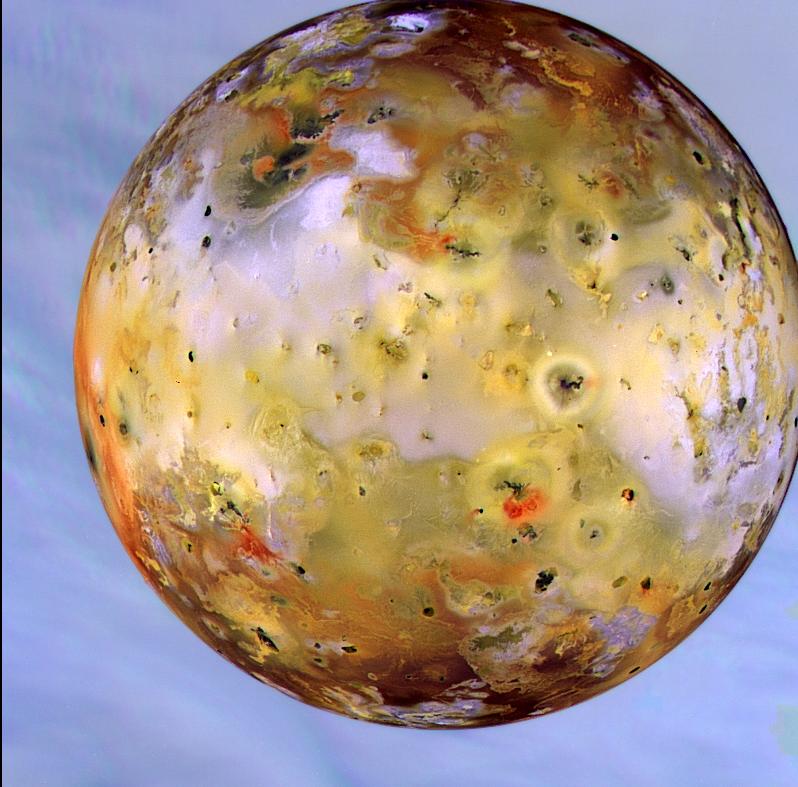

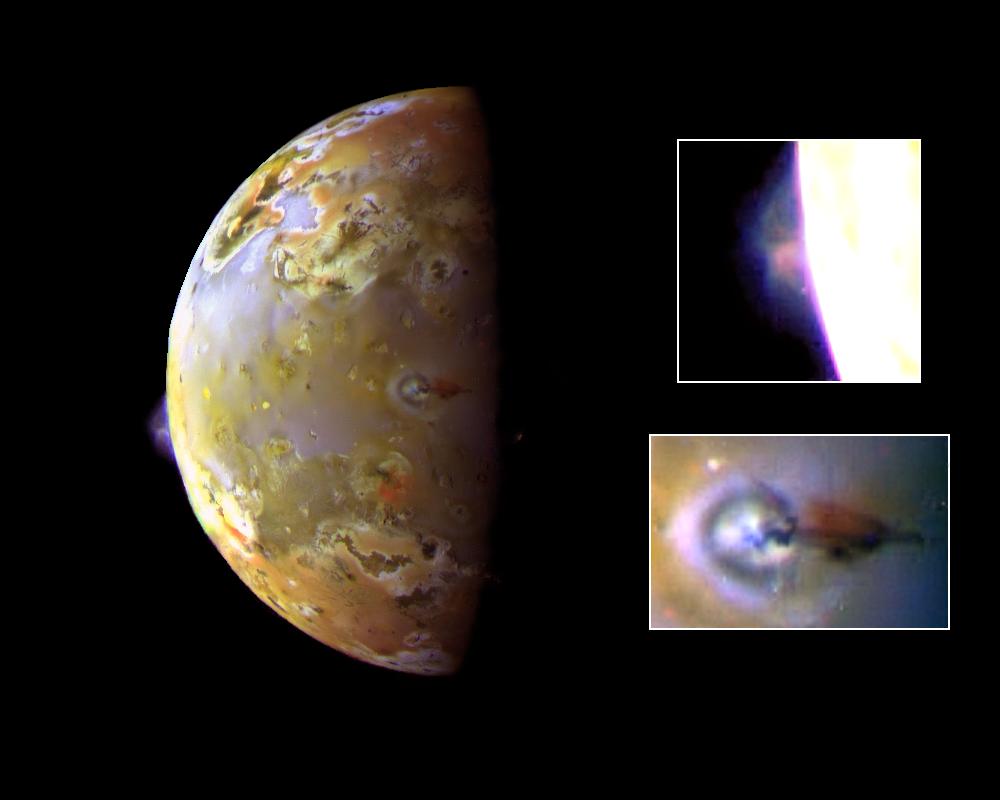

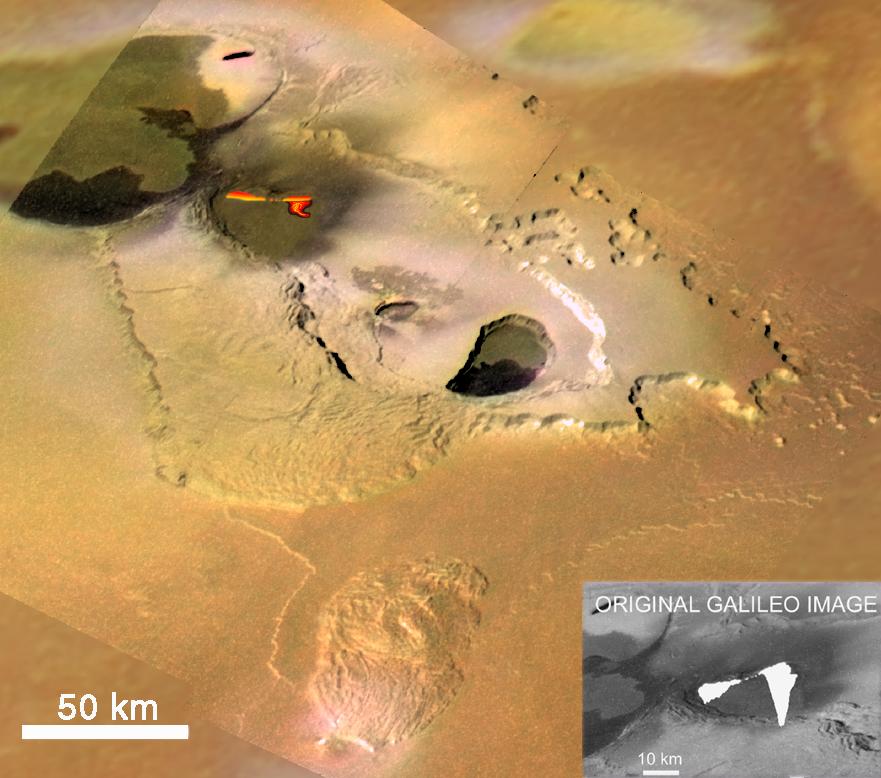

In our discussion of Jupiter's volcanic moon, Io, you may have wondered how Io can remain so volcanically active over millions or billions of years. What is powering all of Io's volcanoes?

They are powered by tidal heating. Jupiter's strong gravity, along with the gravity of nearby moons such as Europa and Ganymede, result in a constant twisting and flexing of Io's interior. This slow flexing gets converted into heat, which escapes to the surface through Io's volcanoes. [See this web page for a more detailed explanation of tidal heating on Io.]

Image from Galileo spacecraft, courtesy of NASA/JPL

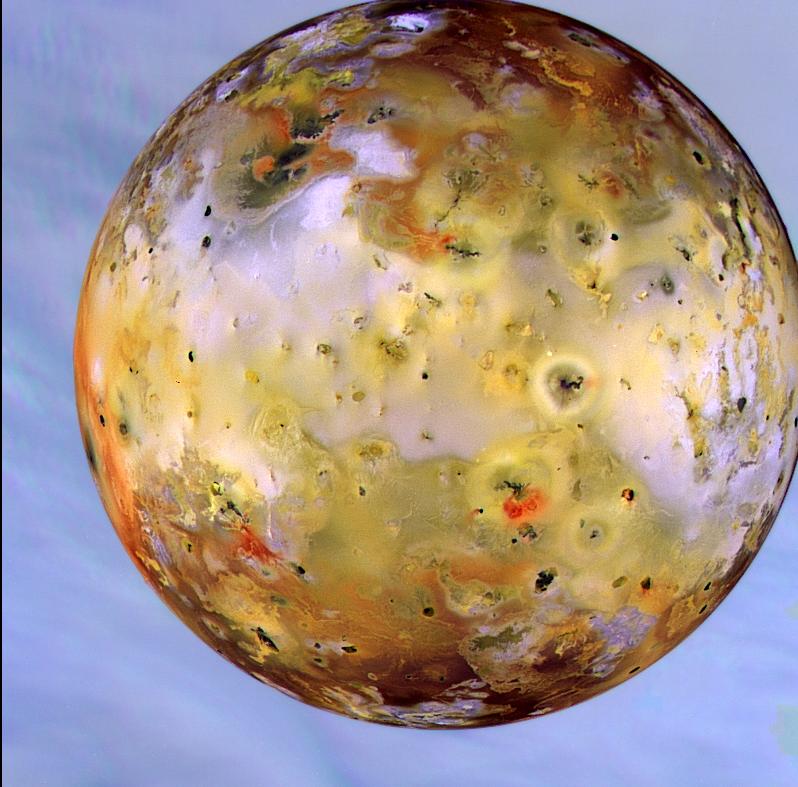

Image from Galileo spacecraft, courtesy of NASA/JPL

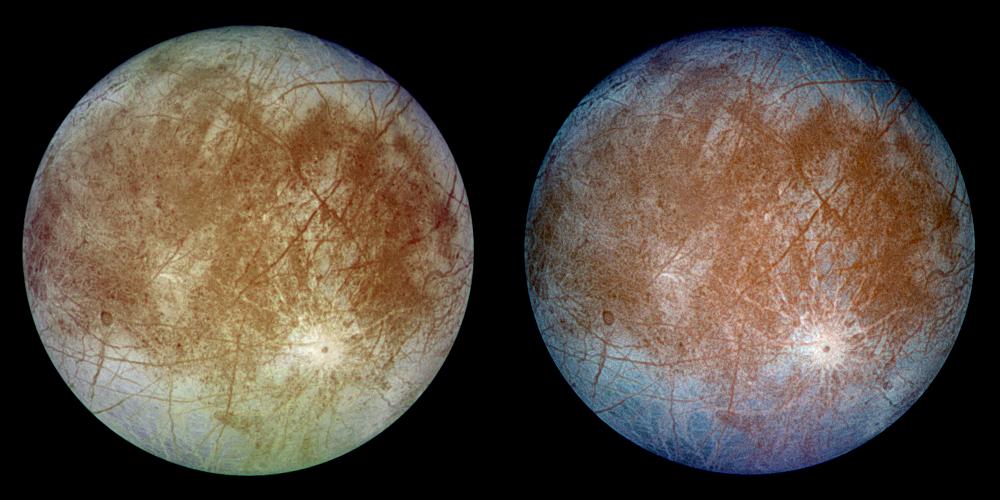

Image from Galileo spacecraft, courtesy of NASA/JPL

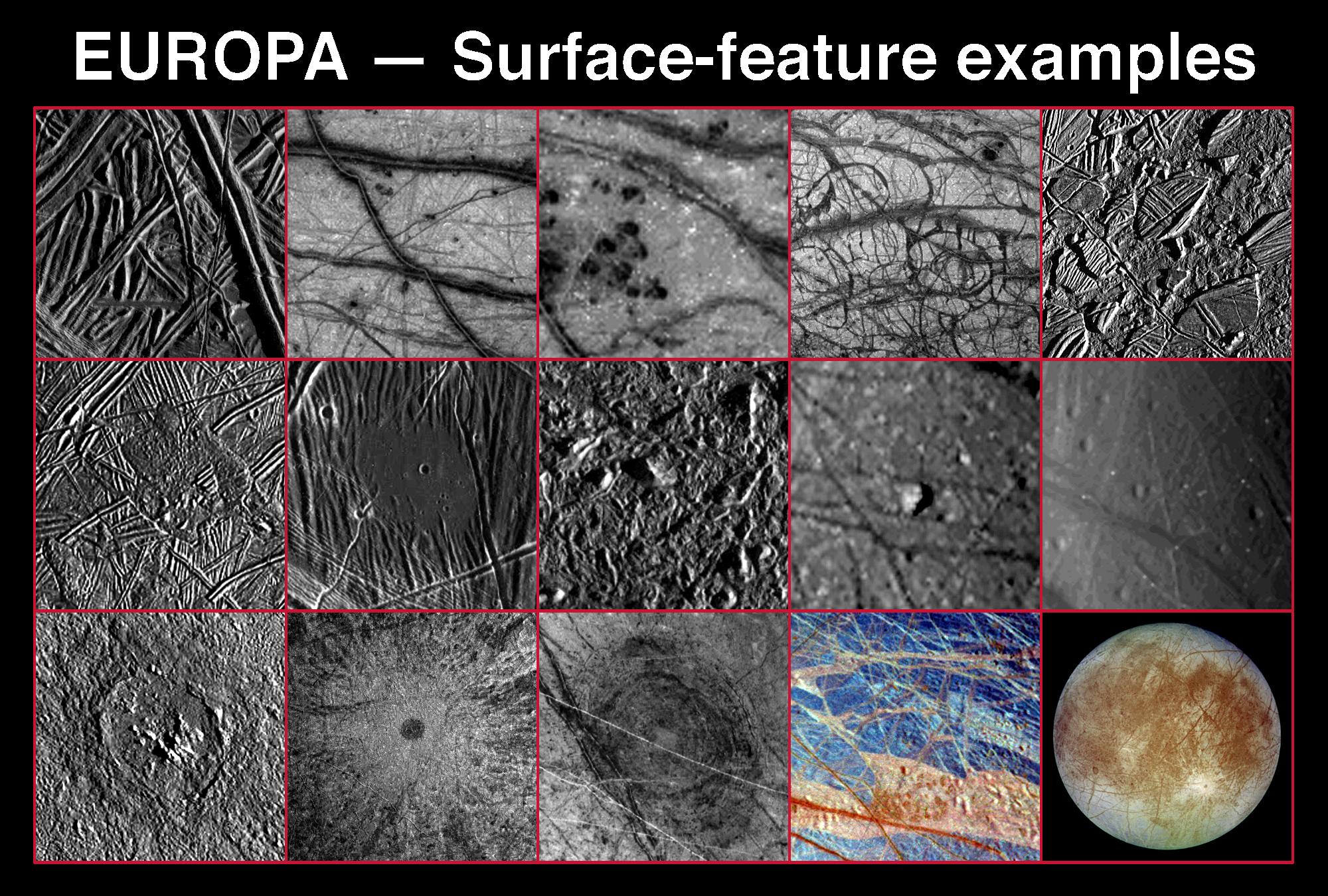

Europa is extremely interesting to astronomers from the perspective of astrobiology. One of the most important results from the Galileo mission, which studied the Jovian system between 1995-2003, was the discovery that Europa likely contains a salty, liquid subsurface ocean. Ganymede and Callisto also contain a sub-surface ocean, but Europa's ocean appears to have made contact with the surface in the recent past. Thus, Europa's ocean is probably closest to the surface, while those of Callisto and Ganymede and probably deeper in the moons' interiors. Could there be any organisms in those waters?

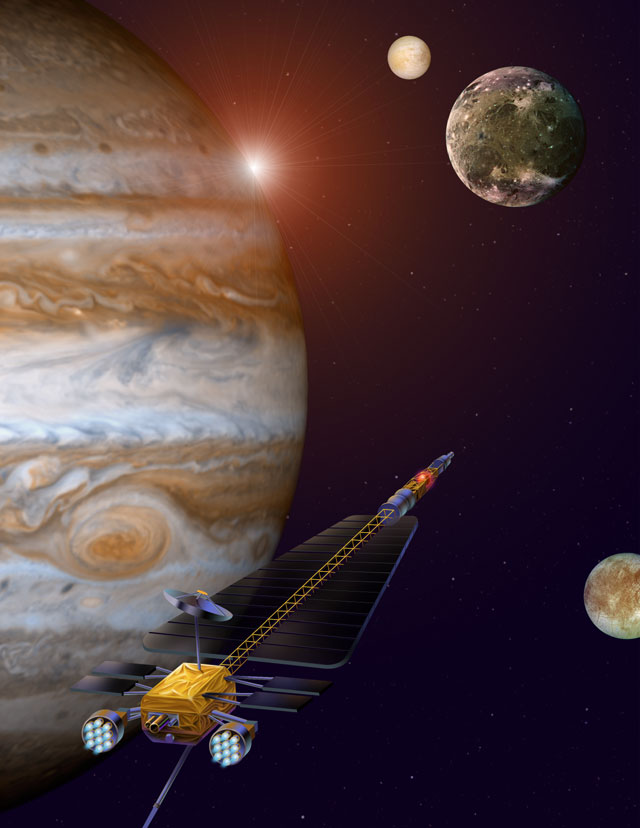

NASA plans to find out! A new mission, the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, is currently being planned for a return to the Jovian system to study its moons in more detail.

Artist's concept of JIMO mission, to be launched in 2012 or later.

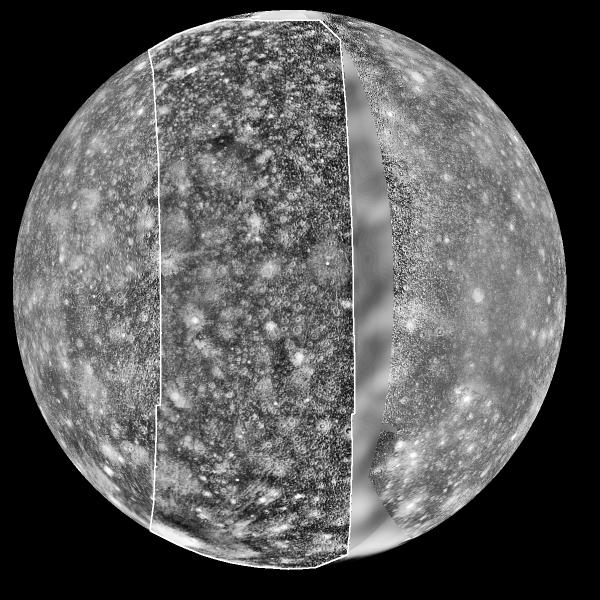

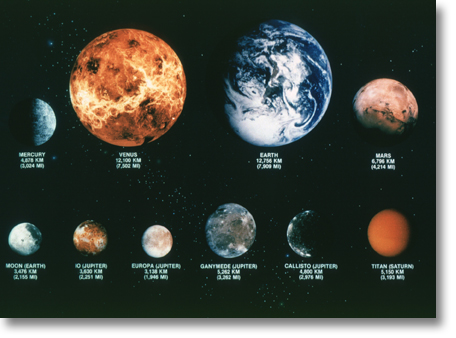

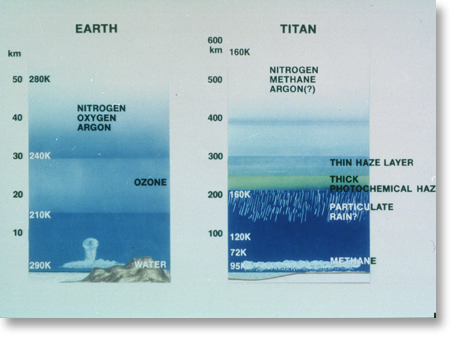

Titan is the second largest moon in our solar system (smaller only than Jupiter's Ganymede), and it is the only moon in the solar system with a substantial atmosphere. Its atmosphere is roughly 1.5 times thicker that of the Earth's, and it is also made of Nitrogen, like the Earth's. It is a lot colder, though, so rather than having a water cycle, Titan has a methane cycle. This means that there may be solid, liquid, and gaseous methane all existing on Titan. Titan's atmosphere contains many complex organic hydrocarbons, which the Earth also contains. We believe that these hydrocarbons were the building blocks for life and the formation of DNA (on Earth), thus their presence on Titan is extremely tantalizing.

Image courtesy of NASA/JPL

Image courtesy of NASA/JPL

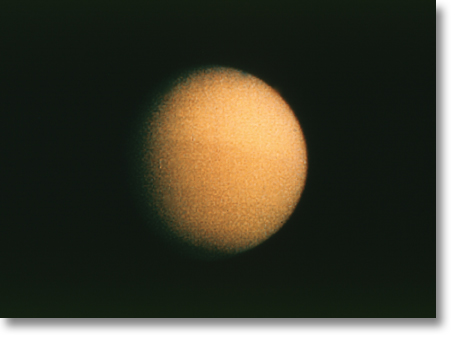

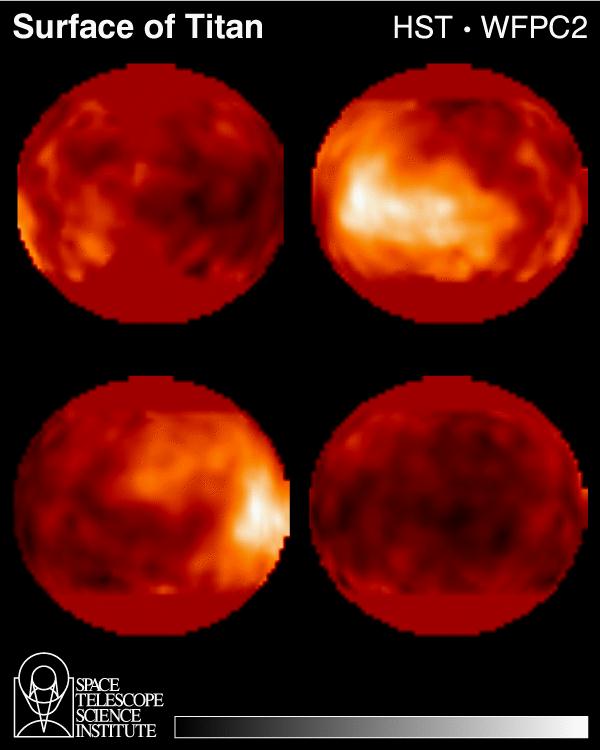

Titan was first explored with the Voyager spacecraft in 1980 and 1981, but the imaging cameras on board the spacecraft could not penetrate through Titan's thick haze (like the smog in Los Angeles, but much thicker!). Recent infrared images taken with the Hubble Space Telescope have been able to see through the haze to Titan's surface, and we see bright and dark continent-sized areas. Are these continents? Mountains? Seas? Oceans? We do not know yet.

Image from Voyager spacecraft, courtesy of NASA/JPL

Image from Hubble Space Telescope

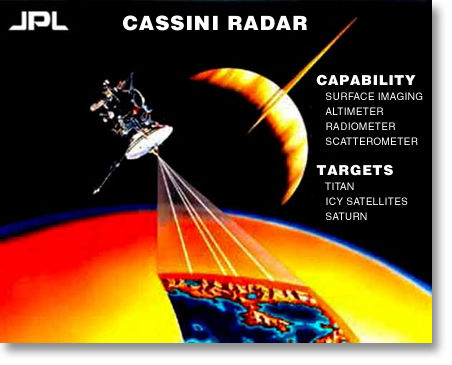

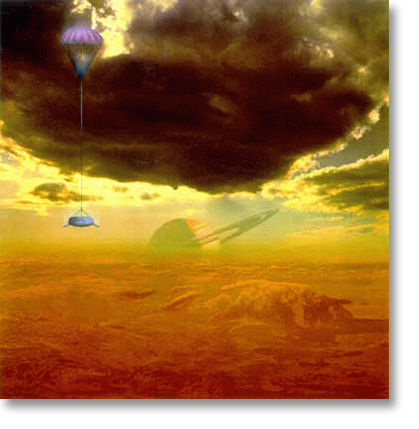

The Cassini spacecraft will arrive at Saturn in July 2004, and will drop a probe into Titan's atmosphere at the end of 2004. With the probe information as well as the orbiter's radar system, we will finally have an opportunity to see what is below Titan's clouds and hazes.

Image courtesy of NASA/JPL

Image courtesy of NASA/JPL

Image courtesy of NASA/JPL